In 1921, a couple years after the October Revolution, Russia experienced a famine.

From Astrakhan to Kazan, the combination of a severe drought, a harsh winter, bad harvests and the fallout from the First World War, the Revolutions and the ongoing Civil War, as well as the shortcomings of fixed price grain requisitioning and inefficient rail systems, led to millions perishing.

Soviet Russia’s economic policy at the time was War Communsim, a centralized management of the newly nationalized economy where total state control was the economic norm. Until 1921, Soviet Russia had banned private enterprise, leaving the Party as the sole economic agent in the turbulent economy.

The famine challenged this status quo. By 1922, the Politburo and especially Lenin – as well as Bukharin, the editor of Pravda – embarked on a change in course, and introduced the NEP – the New Economic Policy. It has been suggested that Lenin was opposed to the Policy, moving forward with it only to prevent any more deaths.

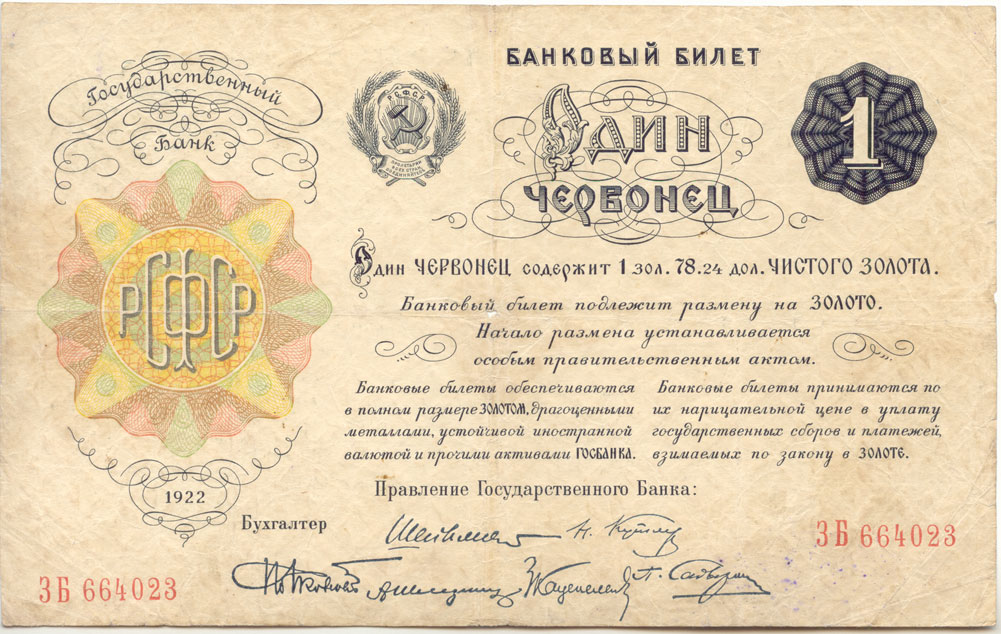

The NEP brought an upheaval to the otherwise Marxist financial situation. Russia found herself back under a stable and gold-backed currency, the chervonet (example pictured below), while the state allowed for a mixed economy with the prospect of foreign investment.

On Agriculture, the state allowed for private landholdings and abolished the grain requisition, opting instead for a barter tax on agricultural products, thus allowing for trade and storage of what was left.

On Entrepreneurship, the State permitted the existence of private urban firms, soon giving rise to private traders known as the “NEPmen”. These entrepreneurs delved in handicraft sales in the countryside, while on cities some even amassed small fortunes. This drew the ire of the Party, as the existence of wealthy businesspeople on the private sector was a crude violation of the communist ethos. Until the abolition of private commerce in 1931, the NEPmen were targeted by Party propaganda (like the following), and until the collapse of the Union in 1991 represented Russia’s last capitalists.

This liberalization of the market, in practice a violation of communist theory, was defended by Lenin & Bukharin as a prerequisite to remedy the malaise of Russian society/economy and to lead to the full adoption of communism, a form of terminal capitalism in its last stage before evolution.

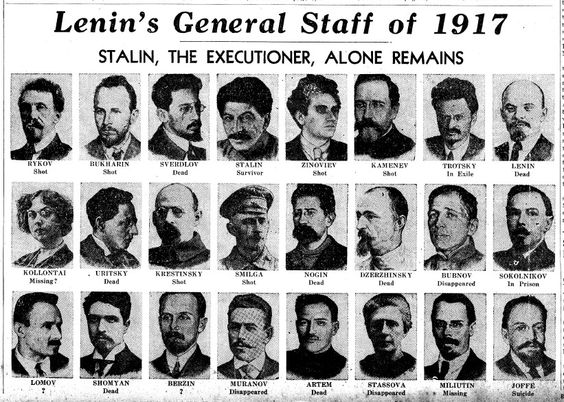

The argument was based on Marx, who argued that only after a nation had fully experienced capitalism and its maturation could it then transition into socialism. Trotsky viewed the NEP as a temporary and regrettable compromise, and in his “Towards Socialism or Capitalism?”, warned against the long-term implementation of it. Given his Menshevik background and until his assasination, he viewed the NEP as one step before the full return of the capitalist system, instead advocating for relentless industrialization and an interventionist foreign policy.

Stalin never went onboard with the NEP. While he was not outright skeptical as Trotsky nor outright in favor as Bukharin, in his eyes the NEP was still a deviation from communism. After having successfuly risen to the top and purged his enemies, in 1928 he insituted the “Great Break” and formally ended the NEP, bringing in its place the Five Year Plan, giving the Union a solid backbone for state control and nationalization.

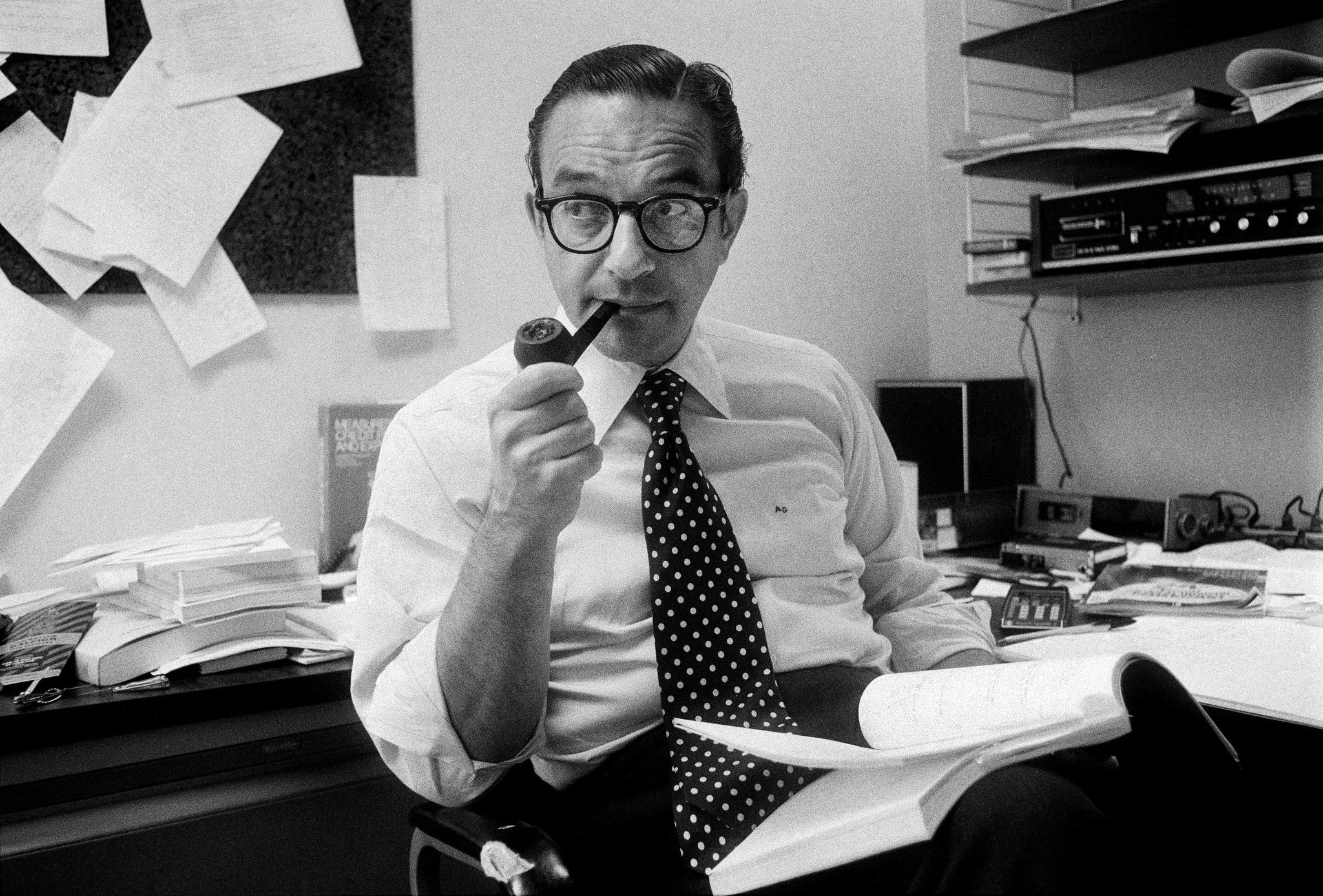

Bukharin on the other hand initially advocated for War Communism, yet after the Famine he became the NEP’s strongest supporter. After Lenin’s death in 1924, Bukharin joined the Politburo and aligned with Stalin, providing the blueprint for his dogma of “Socialism in One Country”, meaning that the transition from socialism to communism should first occur in Russia and thus force the state to neglect foreign revolutionaries to a degree, in the name of pragmatism. Via the Politburo and his alliance with Stalin, he protected the NEP and viciously attacked Trotsky and the radicals in the Party. In 1928, due to the Grain Shortage, he formed the “Right Opposition” as a grouping of conservative Leninists against Stalin’s plan for collectivization. This provided the pretext for his subsequent fall from power, and after he assisted in the drafting of the 1936 Soviet Constitution, he fell victim to the Purges of the Stalinist regime, being executed in 1938.

All in all, the NEP later served as a scourge in the Soviet Union, and as a form of inspiration for the Chinese transition from Maoism to the present day. Gorbachev also looked to it for inspiration, yet the time was not enough to save the Union he had sworn to defend from herself.